Vietnam and the New Geometry of Global Manufacturing

- Nov 23, 2025

- 5 min read

Global trade is entering one of those uneasy phases when the old map no longer explains the world, but the new one has yet to fully form. For decades, the logic was simple enough: build where it’s cheapest, scale where it’s easiest, ship where demand is. That formula pulled much of the world’s manufacturing gravity toward traditional hubs, which rose from one workshop among many to the workshop of the world.

Countries across the world are making their case. India leans on a large domestic market; Mexico benefits from proximity to the U.S.; much of Southeast Asia is supported by young workforces and steady investment. Vietnam is part of this broader realignment. The country’s export sector has held up through recent fluctuations, the policy environment has remained relatively consistent, and the electronics ecosystem, once smaller, has steadily expanded on factory floors.

Recent numbers offer a clearer picture. In the first nine months of 2025, Vietnam’s industrial output rose an estimated 9.1%, with manufacturing alone expanding 10.4% and contributing 8.4 percentage points to overall industrial growth. Foreign investment in manufacturing and processing reached US$31.5 billion in the first ten months of the year. At the business level, the momentum is also visible: more than 255,000 firms were newly established or returned to operation in the first ten months of 2025, up 26.5% from a year earlier, reflecting a domestic capacity that is expanding alongside foreign investment.

Taken together, these figures point not to a sudden boom but to a gradual, durable repositioning: Vietnam is becoming one of several reliable nodes in a supply-chain map that is being reconfigured, shaped more by diversification and risk-management than by any single decisive trend.

I. Vietnam as a Strategic Route

Vietnam’s role in this quiet rearrangement reflects the contours of the world the country is entering. McKinsey’s scenario work shows that corridors connecting emerging markets with each other, including those linking China, ASEAN, and South Asia, could grow at 4–5 percent annually through 2035, above the 2.7 percent global average.

Vietnam sits inside several of these more resilient networks. The country’s participation in ASEAN, along with agreements such as RCEP, CPTPP, and EVFTA, offers exporters relatively predictable market access. Proximity to China allows manufacturers to keep existing supplier relationships even when shifting assembly operations.

As Tyler McElhaney, Country Head of Apex Group, put it in 2025: companies see Vietnam as “a balance.” The country carries the cost advantages of emerging markets while offering a level of policy predictability more typical of mature economies. Even with 20 percent tariffs, the country remains competitive once labor, logistics, and compliance are measured against regional alternatives.

Sector dynamics amplify the logic. Electronics, textiles, and machinery, industries knitted tightly into cross-border networks, are also the ones most exposed to geopolitical tension. Electronics alone has 58 percent of its future trade value exposed to scenario differences, and China still produces around 75 percent of the world’s laptops. As firms rethink where the final assembly should sit, Vietnam becomes a recurring candidate. In some cases, the question is no longer whether to move a factory, but how to redesign a whole supply chain with Vietnam as one of the anchor points.

II. Transformation Visible on the Ground

These abstractions take physical form in Vietnam’s industrial belts. In Ho Chi Minh City, Binh Duong, Dong Nai, Hanoi, and Hai Phong, factories run at high utilization, and industrial parks continue to fill up. Buildings that were once backups or overflow sites have grown into multi-phase complexes serving the United States, Europe, and the wider region.

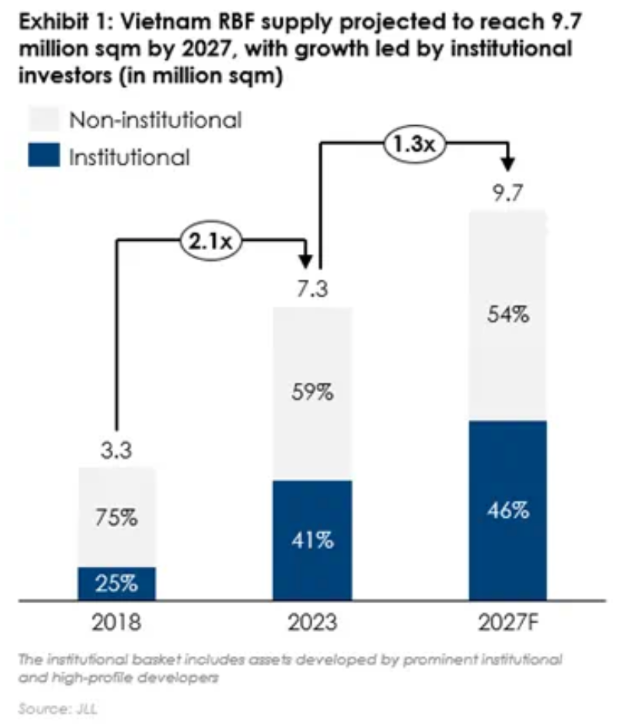

According to BW Industrial and Cushman & Wakefield, the country’s ready-built factory (RBF) sector has moved from utilitarian sheds to higher-spec facilities suited for advanced production. Institutional developers are expected to represent around 50 percent of the market by 2027, a sign that supply is being reshaped for a more demanding class of tenants.

Demand is just as telling. Roughly 60 percent of leasing inquiries now come from Chinese-speaking regions, Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, reflecting shifts in sourcing, cost structures, and risk management. Many inquiries come from “queen bee” tenants: large firms that serve as hubs for entire supplier ecosystems. Northern provinces such as Hanoi, Bac Ninh, and Hai Phong attract firms needing proximity to China; the southern cluster, Ho Chi Minh City, Binh Duong, Dong Nai, draws companies looking for logistics sophistication and established industrial networks.

Tenants often begin operations within six to seven months, a pace that keeps Vietnam competitive in a region where paperwork alone can sometimes take that long. Still, the momentum brings its own pressures: the grid is running hard to keep up, key transport routes are getting crowded, and the demand for skilled workers is rising faster than training programs can supply them.

III. Vietnam’s Position in a Broader Realignment

Zoom out, and Vietnam’s rise is part of a broader reordering in which countries are reconsidering the distance, both geographic and political, built into their supply chains. Trade corridors that link emerging markets to one another, as well as those connecting ASEAN with fast-growing economies in South Asia and the Middle East, tend to remain more stable across different global scenarios. These routes rely less on distant partners and more on regional complementarities: shorter logistics loops, shared production networks, and overlapping economic priorities.

Vietnam sits at the intersection of several of these resilient pathways. The country sources components from nearby industrial hubs, exports finished goods to advanced economies, and is increasingly woven into ASEAN’s expanding internal trade. In more fragmented global scenarios, where countries lean harder on regional networks, Vietnam remains within the cluster of economies that continue trading actively with one another. In diversification scenarios, where buyers spread their risk across multiple suppliers, the country emerges as one of several viable options in a broader portfolio of production locations.

IV. The Road Ahead: Deepening Capabilities for the Next Era

Vietnam’s long-term role will depend on how effectively the country expands capacity and strengthens reliability. Electronics and machinery, two of the sectors most exposed to global shifts, will require sustained investment in:

ports and logistics

electricity reliability and renewable energy

digital and industrial technology

engineering and vocational training

regulatory clarity and risk management

There are signs that Vietnam is preparing for a broader economic identity. In June, the government approved the creation of two international financial centers, in Ho Chi Minh City and Danang, expected to begin operating from September. These centers aim to provide specialized regulatory regimes and attract global financial institutions, signaling a desire to build a more diversified economic base beyond manufacturing.

Whether this ambition takes root will depend on implementation and the confidence of investors. Vietnam is clearly adjusting to the moment. As global supply chains continue to twist and re-form, the country is trying to balance opportunity with realism, expansion with restraint. The next decade will reveal how much of the new trade geometry Vietnam can claim, as a country finding its own coordinates in a world that is being redrawn in real time.

References list:

BCG. (2024). Shifting dynamics of nearshoring in Mexico. Boston Consulting Group. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/shifting-dynamics-of-nearshoring-in-mexico

Cushman & Wakefield. (n.d.). Shifts in Vietnam’s industrial manufacturing landscape. https://www.cushmanwakefield.com/en/vietnam/insights/shifts-in-vietnams-industrial-manufacturing-landscape

C WorldWide. (n.d.). Investigating the nearshoring theme in Mexico. https://cworldwide.com/us/insights-news/item/?id=16344&title=investigating-the-nearshoring-theme-in-mexico&utm_source=chatgpt.com

McKinsey & Company. (2025). A new trade paradigm: How shifts in trade corridors could affect business. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/geopolitics/our-insights/a-new-trade-paradigm-how-shifts-in-trade-corridors-could-affect-business

New York Times. (2025, November 12). Trump tariffs push manufacturers toward Vietnam. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/12/business/trump-tariffs-china-vietnam.html

PwC India. (n.d.). Advantage India: A study on India’s manufacturing opportunity. https://www.pwc.in/research-insights/advantage-india.html

Tổng cục Thống kê Việt Nam. (2025, October). Chỉ số sản xuất công nghiệp tháng Chín năm 2025. https://www.nso.gov.vn/du-lieu-va-so-lieu-thong-ke/2025/10/chi-so-san-xuat-cong-nghiep-thang-chin-nam-2025/

Tổng cục Thống kê Việt Nam. (2025, November). Báo cáo tình hình kinh tế - xã hội tháng Mười và 10 tháng năm 2025. https://www.nso.gov.vn/bai-top/2025/11/bao-cao-tinh-hinh-kinh-te-xa-hoi-thang-muoi-va-10-thang-nam-2025/

VIR. (2025). Vietnam’s time to lead in industrial capacity is now. Vietnam Investment Review. https://vir.com.vn/vietnams-time-to-lead-in-industrial-capacity-is-now-134313.html

.png)